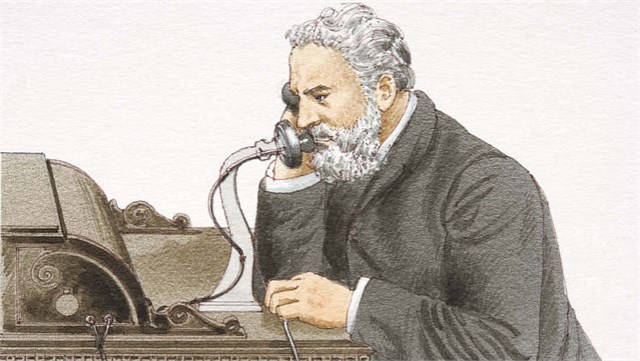

The Losses That Gave Birth to the Telephone

Alexander Graham Bell—the man the world remembers as the father of the telephone—began his journey not with triumph, but with devastating loss.

In 1867, at just twenty years old, Bell stood helpless at the bedside of his brother Melville, a talented artist slowly being consumed by tuberculosis. The rasping coughs echoed through the small room, then faded into silence forever. That silence didn’t just steal his brother’s life; it carved a permanent fear into Bell’s heart: the fear of separation, the fear of never hearing a voice again.

But tragedy did not stop there. Bell’s mother, Eliza Grace Symonds, also lived trapped in silence, robbed of her hearing. She could never hear her son call out “Mother!” Each time Bell tried to speak with her, he had to lean close, articulate every word, and watch her respond with a quiet smile—without ever hearing his voice. That image burned deeply into him, shaping a determination that would define his life.

Out of grief was born a burning question: how could people connect, how could voices be heard, despite distance, despite the silence imposed by fate?

Bell threw himself into research. By day, he taught to make a living; by night, he bent over coils of copper wire, magnets, and fragile membranes, working relentlessly. Every failure seemed to crush his hope, but then the memory of his mother’s deafness, his brother’s absence, pushed him forward again.

And then, in March 1876, history changed. From his crude prototype came the words: “Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you!” That sentence was more than the first message ever sent by telephone—it was the voice of a young man who had transformed sorrow into miracle.

The telephone was not merely an invention; it was Bell’s silent tribute to his deaf mother, to the brother he had lost, and to every soul who longed to be heard, to be connected, even in a world filled with distance, silence, and loss.