Phillis Wheatley – From Slave to Poet

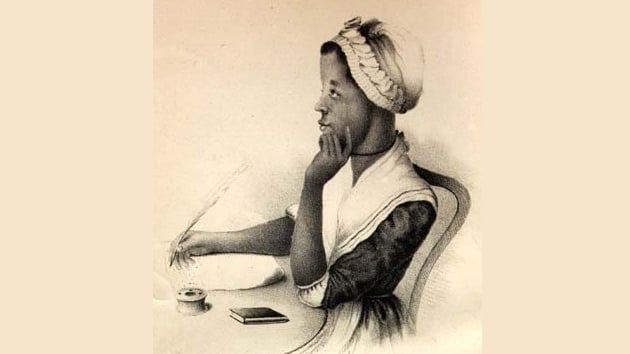

In 1753, in the distant lands of West Africa, a little girl barely seven or eight years old was torn from her family’s embrace. She was locked in the dark belly of a slave ship named Phillis. The cries, the chains, the suffocating silence of hundreds of souls echoed across the Atlantic. From that moment on, the ship’s name became her own: Phillis.

When she arrived in Boston, Phillis was sold to the Wheatley family — and so she became Phillis Wheatley.

But inside that household, something extraordinary began to bloom. Phillis learned to read, to write, and within just a few years, she mastered English — the very language that had once shackled her. By the age of thirteen, she was composing poetry. Lines so delicate, so brilliant, that many refused to believe they could have come from the hand of an enslaved girl.

Whispers spread: “How could a Black slave write like Milton, like Virgil?” Surely, people said, someone else must be behind her words.

And so, at the age of twenty, Phillis faced a most unusual trial. Not to judge her guilt — but her genius. Before her stood eighteen of Boston’s most powerful men: ministers, scholars, statesmen. They fired questions at her, demanding proof. Could she truly understand Scripture? Did she really know the classics? Was she capable of creating such verse on her own?

With calm resolve, Phillis answered each challenge, each doubt, with wisdom beyond her years. At last, the tribunal conceded: the poems were hers.

In 1773, Phillis Wheatley achieved the unimaginable. Her collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in London — making her the first African American to publish a book. Within its pages were not just poems, but the voice of a soul once enslaved, yet never broken.

Phillis Wheatley did more than write poetry. She proved a truth to the world: that even in the deepest darkness of bondage, the light of intellect and freedom can still rise, unyielding and eternal.